Vintage Pachinko: Going Back and Forth Across the Pacific

Did you know: I like pinball! Pinball’s a game with a long history over which the game has changed a lot; its earliest antecedent, bagatelle, was an attempt by pre-Revolution French aristocrats to play bowling indoors using a billiards table. And as the game’s traveled the world, it gained elements and was shaped by its environment. Not only by the taste of players, but also by government regulation– nowhere is that more clear than in Japan. Let’s take a look at vintage pachinko. BONUS: Sega!

Quick History

Bagatelle, played with a pool cue on an elaborate table, required a lot of setup to play. So over time, the game simplified. The pool cue was replaced with a spring-loaded fixed shooter. The bowling pins were too hard to setup each time, so they became fixed nails, and instead the goal became to land in certain holes on the board. Here’s an 1871 U.S. patent model that shows where attempts to make the game more and more convenient eventually went.

Where before, bagatelle had clearly been a game of skilled shots, a ball bouncing off a pin is extremely unpredictable. (In fact, it follows a normal distribution, so in mass numbers is extremely predictable, but shush) The new “pin game” was a game of chance as much as it was a game of skill, if not more. However, any use for gambling was overshadowed by the invention of the slot machine in the 1890s, so it remained mostly a novelty attraction.

In the 1920s, the United States and Japan enjoyed a period of good relations, and bagatelle machines like the above were imported. The most popular was called “Corinthian bagatelle” due to a pattern of pins that very roughly mimiced a Corinthian column; therefore in Japan the pin game became known at first as the Corinth game. (コリント ゲーム) It seems to have gained some popularity in candy shops, where children could win bits of candy for good shots; the kids are given the credit for the onomotopoetic name “pachinko” (パチンコ).

The point of divergence

U.S.-Japan relations went downhill fast during the early Showa period, which began in 1926. Here’s where pinball was headed in the United States, 1932’s Ballyhoo. Ballyhoo was such a big hit it gave its name to Bally, which would become the largest manufacturer of pinballs for a time. (Today they run casinos, because everything comes full circle)

Notice that compared to the 1871 patent machine above, it’s become a fully self-contained unit, taking coins and having the balls be self-contained within the machine. (Taking coins would lead to giving coins as well, with the rise of gambling pinball, but that’s another story, one I don’t have room in my house for)

Even this early, meanwhile, pachinko machines were taking on two characteristics that would definitively separate them from pinball:

- The machines became vertically oriented. This may have been borrowed from the British “All-Win” machines.

- Rather than be paid for with coins, the balls were made wholly external; you provided balls, and you won more balls.

Slot machines were (and mostly still are) illegal in Japan; these helped pachinko fit the slot machine’s niche. Vertically mounted, they could be densely packed in “parlors”. And a major addictive point of slot machines is that a small winning can be fed right back into the machine; when you win additional pachinko balls, you can use those to keep playing.

Not so fast

Section added 3/30/2023

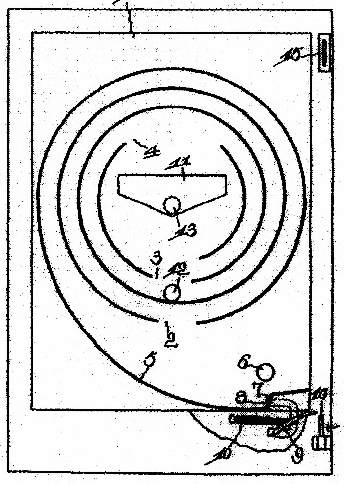

In discussions with cpi on Mastodon, some of my assumptions have come into question. Specifically, I assumed that pachinko is primarily an outgrowth of bagatelle and pinball; cpi argues that the All-win is much more important than I gave credit for. And she may have a point– look at the first patent for a pachinko machine in 1929.

Notice that there are no nails on the playfield, and the ball seems to be enclosed; this really does look more like something out of the UK. The pachinko launcher is very similar to the all-win launcher, and given pachinko also means slingshot, could easily get the same name. It’s worth noting that this isn’t the only style of machine in 1929; this gallery shows several “bring-your-own-ball” types and machines with nails. However, Japanese bagatelles and Corinth games seem to not have used the auto-launchers like the US.

Still, I do think that bagatelle and the nails from it are an important part of the development of pachinko. While pinball may not be its direct sibling, they’re at least cousins.

Ah, so, where were we? Ah, right:

It’s quite a bit like biological evolution; the slot machine niche was open in Japan, because regular slot machines were prevented by the government. The pachinko parlor added a dash of indirection and skill to sneak by, but make no mistakes: this is a gambling niche. A lot could be said about that, and the effects of gambling in general (Japan has much higher rates of problem gambling than similar countries); but I’m not the right person to say it. I don’t personally gamble as a rule; I just like to play games. Is this a game I, as an American, want to play?

Back to America

Pachinko was banned from 1937 until the end of World War 2 due to wartime economy measures. (Production of pinball also stopped in the U.S. once they became involved in the war) It returned post war, as did imported American pinball games. Sega, then called Service Games, got its start importing slot machines and other coin-operated games to US military bases established in the island nation. Some American soldiers did get hooked on pachinko and a few machines were imported back home by them, but the real rush didn’t start until the 1970s.

Here’s an ad from Montgomery Ward, then a major department store chain, advertising pachinko machines. How the heck did this happen?

Regulations in Japan made it difficult for a machine to be certified for more than one or two years; heavy usage meant that the gambling halls were happier to replace them anyway. Some enterprising entrepreneurs made the connection: Americans love pinball, so why shouldn’t they also come to love its Japanese cousin, available cheaply in huge numbers from parlors who otherwise would throw them out? After all, as importer Target Abroad said, it’s an All-American game!

These things were brought over in huge numbers; Americans love their fads. Talking with Dan Welch of Magic Pachinko Restorations, he said that sometimes the refurbishment was done so rushed that he’s found silver metallic spray paint on top of vintage 1970s Japanese cigarette ash still in the ashtrays.

This fad era seems to have died out in the latter part of the 1970s; perhaps overcome by another fad for the newfangled “Atari” and other home video games. But what that means is that there’s still just a huge number of these machines in the United States; some well-taken care of, even more rusting in garages and barns. Let’s take a look at these machines.

Epoch

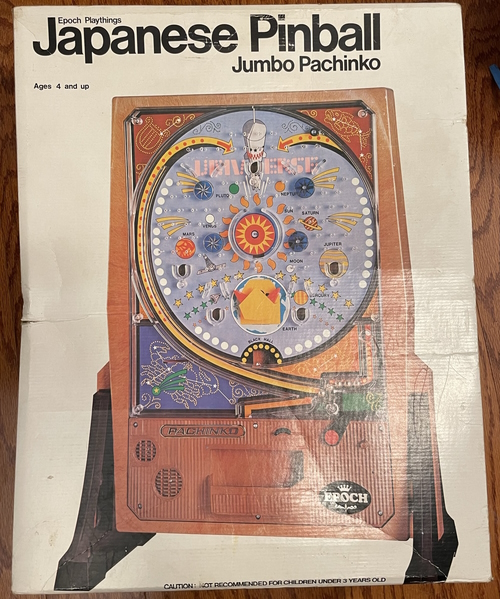

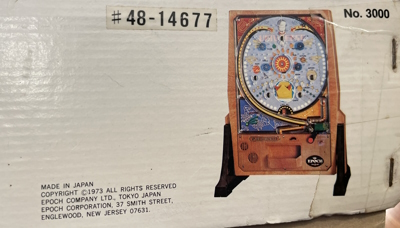

Before we take a look at a “real” machine, let’s take a look at another artifact from the 1970’s pachinko fad: the Epoch.

It’s a plastic Pachinko machine; they made a bunch of different models with many variations, many moving further away from the original Japanese game, with things like white balls and different patterns. But I got this model, “Japanese Pinball: Jumbo Pachinko”, because it looked very close to the real machines. Specifically, it seems to be similar to the machines of the late ’60s, though this one is from 1973.

It’s got a neat universe theme, with a number of “pay pockets”. The ball getting into a pocket will pay out a few balls; you always get your winning or losing ball output at the bottom. The nails are just molded into the clear plastic.

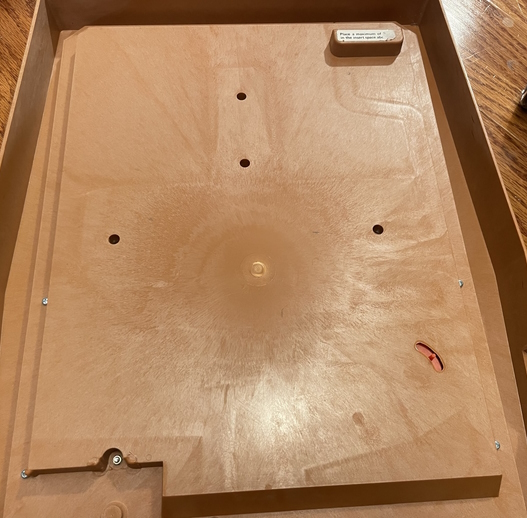

I was hoping to take this apart, but unfortunately it seems to be held together pretty securely, and as the art is just cardboard, I didn’t want to destroy it in the process. I got this machine ages ago and would rather not destroy it. That being said, you can see some of the internals in the plastic. It’s a simplified version of the pachinko mechanism, so I hoped it might be a little easier to understand.

Let’s make it a little more obvious and add some labels.

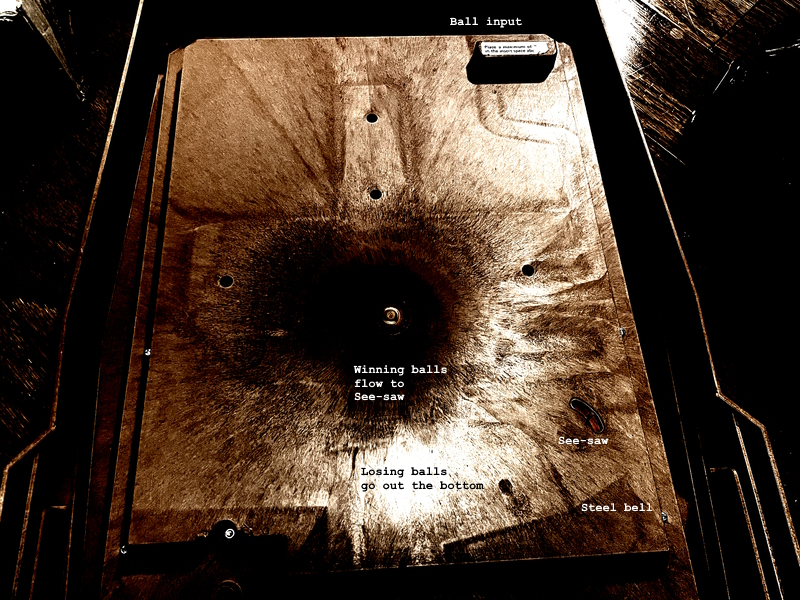

A losing ball simply goes out the hole into the front. Not that interesting. More interesting is a winning ball. No matter what hole it goes into, it is redirected to the see-saw, which blocks the flow of balls from the winning compartment. In this machine, they rest directly on the see-saw.

When you win, the winning ball passes into a route through the see-saw, dropping the balls on top of it and then resetting it for the next jackpot. The dropped balls hit a steel bell on their way down to the bottom compartment. That clanging noise of balls is what gave the game its name; pachi-pachi being an example of Japanese onomatopoeia.

There’s just one see-saw, so jackpots are always the same size. And this is true on real pachinko machines of the period as well; on real ones with say, a jackpot of 15 balls, it’d be known as an “All-15” machine. This one is more of an All-3. (But hey, you get your losing balls back)

Trying to hit pay pockets is a nice challenge, and machines with just pockets were the norm up until the 1960s. But this game adds an element to make things a little more interesting. Check out the tulip.

When it’s closed, the tulip is as hard to hit as any other pay pocket. But unlike the other pay pockets, it rewards you when it’s hit. When a ball passes through a closed tulip, it opens.

An open tulip is much easier to get the ball into. However, this one, like most mechanical tulips, immediately closes after you get your shot.

The tulip is a very clever device. Not only does it not require an extra jackpot chamber to give the player a better reward, it convinces the player to keep playing. If you have an open tulip, you’re not going to stop playing and just leave it for the next player, will you? Modern machines go much, much further than this to keep the player around.

So I hope this shows that there is in fact some skill involved in vintage pachinko. There’s still a lot of chance, of course. Mostly chance.

Power Flash

If one tulip is good, nine tulips must be even better, right? Behold, the Nishijin-Sophia Power Flash “Thunderbird”. I actually just got interested in this machine at first because of the theme; it reminds me of some of my favorite card-themed electro-mechanical pinball tables, like Gottlieb’s Jacks Open. This has some tricks up its sleeve.

Notice that this is a “tray-loading” machine; you don’t need to feed the balls yourself through a small hole; your jackpots come right into the tray to be fired again. This was invented in the 1950s, but was actually banned by the Japanese government for about a decade because it made the machines too addictive. I guess eventually they just gave in.

Here we also see how tulips get a little bit more complicated, beyond just “opens when a ball goes in, closes when a ball goes out”. In fact, you’ll see that two of the tulips here can’t be opened at all that way!

The two tulips, marked with a Q for queen, and a face that many people seem to refer as a queen, but looks more like a joker to me, are blocked by a spinner and tightly-positioned nails. You can’t make it in; trust me on that one. So how do you get those tulips to open; are they just for show?

Put a ball in the King and find out!

What’s cool to me here is that this is all entirely mechanical; the machine had no power when I took that video. So hitting the king tulip is a big deal on this table.

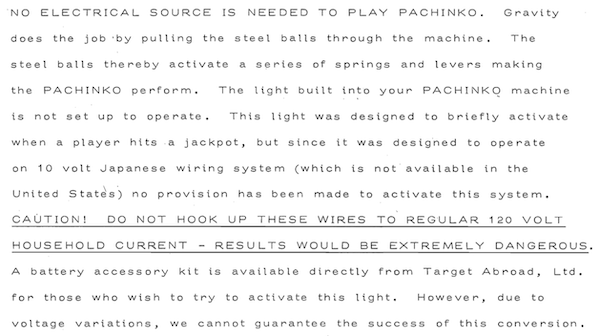

Now, fans of vintage pachinko might be screaming at me. After all, the Power Flash line is know for its use of electrical power. But here’s the thing: if you got this machine in the United States from Montgomery Ward, you wouldn’t have access to that. (In fact, you wouldn’t have even had the choice of machine; as they said “part of the fun of Pachinko: many different playing boards”) Let’s take a look at that manual again:

Many machines did end up being modified to include a 9V battery holder for lights (there’s actually two: one for a jackpot, and one to let you know when there’s not enough balls), and for most machines that was enough. But this is a Power Flash; an electro-mechanical pachinko machine. Even that 10 volt system isn’t enough– it required 24V of power for those trick features. And so if you did get one from an importer like Target Abroad, they just didn’t hook them up. As I showed, you still get some complex gameplay without power at all.

Let’s take a look at the back, and you can see the transformer in the bottom. This was installed for me by Dan of the aforementioned Magic Pachinko Restorations (he made a video on this particular machine if you’re into those), and he also restored the machine fully. These machines all have completely open backs; they were designed for a parlor, after all.

Interestingly though, from this view you wouldn’t see much different from a regular “Model B” Nishijin machine. The big difference from the toy one is the jackpot compartment in the center; jackpots do not rest directly on the see-saw, and instead, a ball going through the seesaw will then set off a separate lever that opens the jackpot container, as well as resetting the see-saw.

Since the see-saw doesn’t have winning balls resting on it, it needs to be able to be set properly; generally the balls will reset it, but if something goes wrong, a tiny nail is present that can be pushed up on to move everything in place. This sort of adjustment would be done by the parlor.

All of the mechanisms that make this a powered machine are deep inside; it’s actually just a few solenoids; two that can open all the tulips on each side, and two that can close each side. Let’s take a look at the playfield. I’ve labeled a few points.

Getting a ball into point A is the best; a ball that does so and then manages to pass into the crown (a pesky nail makes it hard) will activate all the opening solenoids, opening both sets of tulips on the board. It will then pass through the center and open the ace of hearts tulip underneath mechanically.

If it doesn’t make it into the crown, it’ll pass over to one of the holes on the two sides of the inside of the bird, B and C, will open the four tulips on just their respective sides. (The holes on the wings are just regular pay pockets, as is the yellow device in the bottom center)

But there’s a catch here. Electricity can open more tulips, but it will also close them. Specifically, the yellow “Joker” tulips, E and F, will close all the tulips on their respective side. You still get the jackpot for landing in them, but you’ll find it harder to get further jackpots.

Since the only control you have in the game is how hard you pull the lever, pulling off specific shots is a matter of luck. It’s a gambling machine, after all. But it’s also a matter of skill. I often try to do a weak shot that will barely clear the path, aiming for the top left King. A center shot is riskier but more rewarding. When the tulips are open, you’ve got to try to avoid the yellow ones until you’ve made the lower shots; easier said than done.

So how do you play pachinko at home? Target Abroad answered that question too.

Generally, I tend to play it like an executive desk toy (despite me not being an executive); it’s just fun to watch the balls bounce, try to make hit shots, and see if I’ll come away winning or lose all the balls I put in. Thanks to Magic Dan for making sure that the nails are positioned well– that’s how they got you in the parlors.

Sega

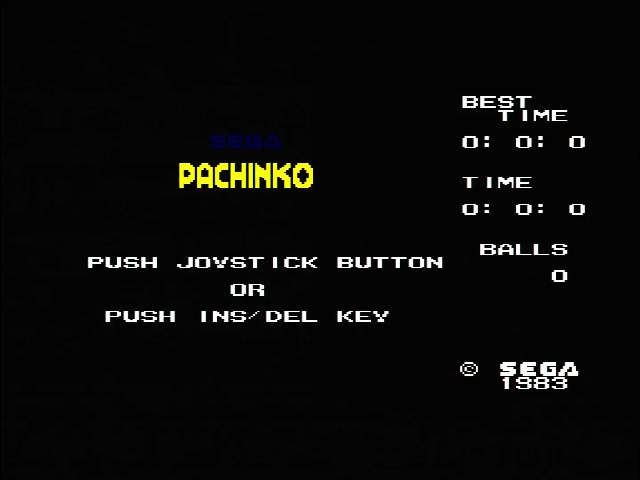

It wouldn’t be a Nicole Express blog post if we didn’t touch on a Sega game, right? Well, today Sega has merged with Sammy, but back at the turn of the 1970s, Sega did make amusement pinballs in Japan, but not pachinkos as far as I can tell. But in 1983 they made what was as far as I know, the first pachinko video game in Japan. So they just called it Pachinko. Because I’m a self-parody sometimes, I’m playing it on a Master System 2 with the compatibility palette in PAL mode.

As far as I know, Sega’s Pachinko, which just has one table, is not based on any particular machine, but is a good reflection of the state of popular pachinko machines in 1983. A pinball afficionado might tell you that pinball changed a lot in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as electromechanical machines gave way to solid state. The same thing happened in pachinko; Sega’s machine differs a lot from the Power Flash.

Many things are similar. It’s a grid of nails on a circular playfield. There are three pay-pockets and two tulips on either side; they’re simple tulips, more like the Epoch game. But there’s also a seven-segment display of three numbers. If you make it into the “GO” pocket, then they’ll spin, just like a slot machine. (Usually on real machines I’ve seen, the GO pocket is in the bottom)

Winning the slot machine won’t give you extra balls; just like a vintage machine, this one always pays out the same amount. But see that “Lucky” square at the bottom? That’s actually a compartment that can open, called an attacker. That compartment’s very easy to hit when it’s open (it’s huge), so the slot machine is worth your time. In fact, it’s worth more time than the tulips. Which is why modern digipachi usually don’t have them.

And then there’s the autolauncher. You don’t shoot balls one at a time; the auto-launcher shoots a continuous stream, and you control its strength. In this version, that’s shown by moving the small red circle on the larger circle. A stronger shot will move further up the playfield, just like if you had done the same with the lever. The autolauncher is such a big deal, that most enthusiasts will put it as the dividing line; before its introduction is vintage pachinko. Afterwards, modern.

Many people in the West say that the autolauncher removed the skill from pachinko; I’m not sure I agree there. After all, even with a manual lever, you want to shoot lots of balls in the same place for probability; there is still gameplay in Sega’s Pachinko. But I do think it changes the game too much for a western pinball enthusiast to recognize it; that’s probably a big part of the reason why there was no second pachinko boom.

The most interesting thing about Sega’s Pachinko for SG-1000, though, is probably just that it’s really expensive, torturing collectors who want to complete their sets. Why? Apparently, Sega recalled it very soon after launch due to some kind of a bug. A few months later, Pachinko II was released; however, it’s not just a bugfix, but includes many graphical changes and additional tables. Unlike Pachinko, it’s cheap as dirt. This might be worth talking about more later.

The past is the present

The Japanese situation that led to the mass import of pachinko machines into the west never changed; machines still have very short lives in the parlors, and various importers will still bring them to the US for you. Today, they will even hook up the electronics, since they’re mandatory to play. But it’s not nearly as popular as it was in the 1970s. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are more vintage pachinko games in the United States than in Japan itself.

Interesting, manually-launched pachinko isn’t entirely dead. Take a look at A-gon’s Heavenly King’s Story. Flashing lights, a center attraction, but a lever and classic tulip gameplay as well. (The “2” tulips take in two balls before closing)

Of course, I suspect this and the other A-gon machines with levers are more of a nostalgia attraction. The vast majority of pachinko machines in Japan today are digi-pachi with autolaunchers, and that’s how they like it. But for now just remember: if you want merit, buy the Nishijin’s merit. I think they also still make pachinkos, but it’s the merit you want.