Fun With 3 Colors: The Vectrex 3-D Imager!

Oh gosh, I never thought I would get the chance to talk about this– this is one of the coolest devices out there in my book. It’s got everything; vector graphics, colors from a monochrome image, motors, CRTs, failed add-ons for a flopped console, and it’s impossible to screenshot. How do you make a black-and-white screen color?

The composite article, again

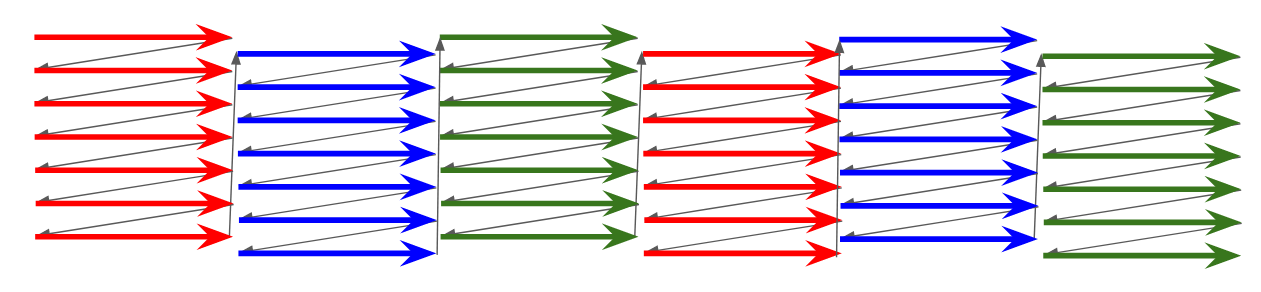

I talked about this a bunch in the composite video article, but the first broadcast color television system approved in the United States was not the NTSC system we all know and… love. It was, instead, a mad 144Hz system known as “field-sequential”, in which the color signals were separated into red, green, and blue, and then displayed one after the other in a wild six interlaced frames.

The big problem with frame-sequential television was that its 144Hz signals were not at all backwards-compatible with the 60Hz monochrome televisions Americans were already buying. This, combined with the Korean War, led to the demise of the system. A secondary problem, though, was the fact that the colors were provided by a giant spinning color disc. This disc had to be large enough that each color segment could cover the entire screen, so televisions using this system have small and offset screens.

(Picture taken from the Early Television Museum. I believe this to be fair use)

The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), the creators of this system, argued that it could be adapted to work with a true color picture tube, such as that would eventually be used by the later RCA NTSC system. Instead, the spinning color disc was a cost-saving measure that would let color television be adopted more quickly by using cheaper monochrome tubes.

Now, that’s one way to solve the issue. But let’s imagine another way. Imagine that the spinning color disc was not on your living room television, but it was instead on your face. Then, assuming everything was kept synchronized, you could have a huge picture tube. It would look awful if you weren’t wearing the special giant spinning disc glasses, but hey, people would put up with requiring special glasses for 3-D television when that was a fad at the early 2010s.

In fact, let’s talk about 3-D as well. Imagine half your spinning disc is opaque. Then, each eye is covered 50% of the time. Field-sequential was interlaced, but you could put the fields in a different order.

We’ve combined 3D with color television, all using a black and white picture tube! And all we needed to do in exchange was to have a super-fast spinning disc right in front of your face. What was actually done was something much wilder.

The Vectrex 3-D Imager!

That’s right. The above system uses the typical “raster” pattern of a television, but you don’t have to do that. In fact, if you have a vector monitor, for example, if you use the Vectrex, you can just draw lines wherever you want, and as long as the timing’s right, you’ll still get your color. Not only is this a theoretical possibility, it’s something that actually existed.

This is not the Vectrex 3-D Imager, though. The 3-D Imager came out in 1984, the same year Vectrex production ended due to the ongoing death of the North American video game console industry, so it only received a limited release. What this is is a modern replica produced by Madtronix in Sweden. So while it’s not the Vectrex 3-D Imager, it’s a Vectrex 3-D Imager, and that’s good enough for me. One of the coolest things about the internet is that passion projects like this can get a market.

So, how does it work? The circuitboard here is black with black traces, but there are some documentation here of the original thing. What I’m working off of is the file called “3DGOGGLE.TXT” by Zach Ethridge, dated to 12/26/95, which I got from a large ZIP file of programmings docs from playvectrex.com, as well as Fred Taft’s disassembly of 3-D Narrow Escape.

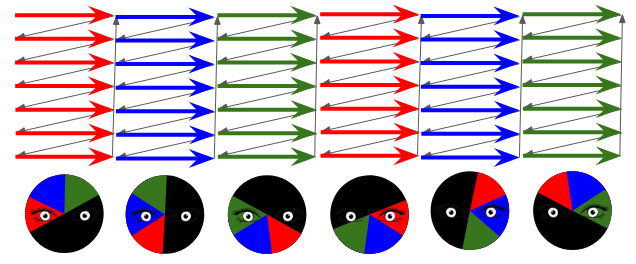

Remember the diagram of the Vectrex from my first Vectrex blog post?

The entire Vectrex is controlled by the 6522 PIA, but we left off some of the connections. We need to fill them in now. The 6522 is also hooked up to the AY-3-8912. The AY-3-8912 is the Vectrex’s sound chip, but it also has 8 IO lines. These are hooked up to the controller buttons, but they can be both inputs and outputs. Finally, an interrupt pin is hooked up to the Vectrex’s second controller port button 4.

The Vectrex communicates with the 3-D Imager (or a clone of it) using the second controller port. The interrupt on button 4 is hooked up to a photodiode; it will fire an interrupt when light reaches a known point on the disc. This is different on my clone than the original; the original one had an index hole on the disc, whereas this one just has the photodiode on the backside and colored light activates it. So this interrupt is how the Vectrex knows where the disc is.

But how does the Vectrex control how fast the disc spins? For that, it uses another pin on the second controller port, pin 2. The 3-D Imager is wired such that pin 2 can be used for pulse width modulation. Essentially, it turns on and off the motor. Using the timers on the PIA, Vectrex games that use the 3-D Imager need to implement logic in them that manually turns on and off, and constantly adjust the speed of spinning based off of how long it’s been spinning. Also, when drawing the screen, it needs to be constantly aware of where in the color disc it is.

The Vectrex was always an intensely timing-focused beast, but the 3-D Imager brings it to a new level. Consider a monochrome Vectrex game. The Vectrex typically runs games at 50Hz, but if you take a bit longer to draw a frame, you have a buffer. The phosphors will fade and it won’t look as good, but it’s fine. If you run out of time on the 3-D Imager, well that disc can’t stop on a dime. And if the interrupt fires while you’re in the middle of drawing a line, you might find yourself in even more trouble. The 3-D Imager games seem to run at a much slower 27Hz, but of course, each eye gets half that, so you’re back to 54Hz.

How well does it work?

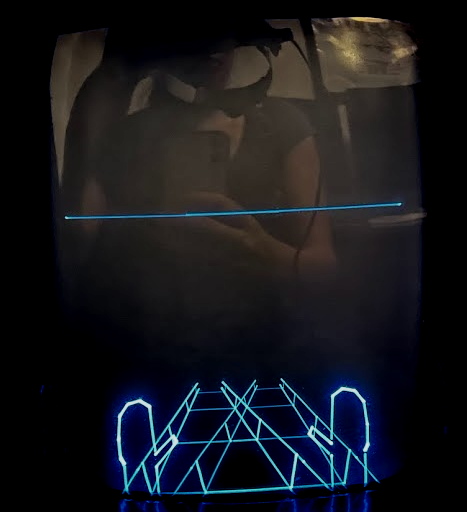

The color on the Vectrex 3-D Imager works really well, in my experience. Here’s the best photo I could take through the imager. This is 3-D Crazy Coaster, one of the three officially-released 3-D Imager games. First, let’s take a look without the disc.

That doesn’t look great! Let’s put on the headset; this is where the photos of the monochrome Vectrex screen end up starting to look good by comparison, so I apologize.

Let’s zoom in a bit at least.

You can see that the hands are blue, the track is red, and the obstacle is green. The 3-D Imager seems to do its best work in using the primary red, blue, and green colors, rather than trying to mix them. I imagine this is a consequence of the limited time budget, though you can see the attempt at a purple horizon just barely.

Where I struggled with the 3-D Imager was the 3-D part. You really need some distance between yourself and the Vectrex screen for it to look good, but then the screen is small. Still, I am really impressed with the color here.

Tricks of the trade

One thing you might have noticed in the photo of the 3-D Imager above is that the disc does not have even red, green, and blue sectors. Meanwhile, the screenshot of 3-D Crazy Coaster was in fact done using a disc with equal sectors, though if you can tell that from the photo I would be incredibly impressed. The secret is that the color discs on the Imager are interchangeable.

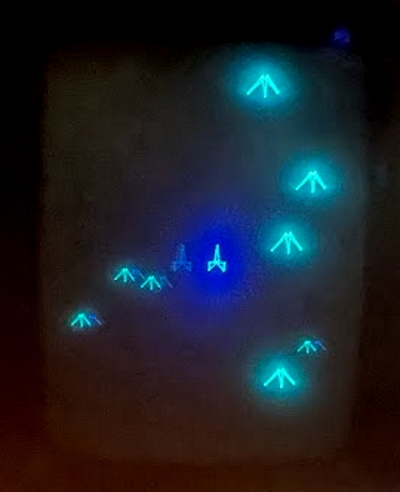

Of the three officially-released 3-D Imager games, both 3-D Crazy Coaster and 3-D Narrow Escape, a shooter that reminded me of Zaxxon 3-D on the Master System, use the one with equal sectors. The one with unequal sectors is 3-D Minestorm, a 3-D version of the Vectrex’s pack-in Asteroids clone. Interestingly, you could imagine a 3-D disc that only had a clear segment on each side for monochrome 3-D games, or one with color on each side for a color 2-D game. Neither was ever made.

The mines in the game are green, and the player’s ship is blue; this explains why the green sector is so large. The 3-D effect here is subtler but seemed to work alright. Let’s compare it to the original Mine Storm screenshot I took, so I can get my money’s worth out of these Vectrex photos.

You can see that the starfield is replaced by the background mines, which are further than your ship and can’t hurt it, and that the small display showing how many lives you have has also been sacrificed.

It’s also worth noting that all of the 3-D Imager games would have originally had overlays, just like the other Vectrex games. However, I do not have any of them to show.

Images are cool!

The Vectrex 3-D Imager is one of my favorite things to ever touch on this blog. It’s just a neat intersection of so many technologies, and with the combination of field-sequential color and vector graphics, is about as far as consumer technology ever got from the raster standards we use today. On the other hand, it is very limited.

For example, while PiTrex does support the 3-D Imager in its Vectrex emulator, and I was able to play 3-D Narrow Escape about as well as on real hardware, it won’t be a good solution for Color QuadraScan games like Tempest because of how strict the time budgets are. (Color QuadraScan was Atari’s branding for vector games that used color vectors, but it worked completely differently, using a color picture tube rather than a spinning disc)

Now if you excuse me, I need to go let the Enterprise know that resistance is futile.